Physical Address

Suite 5, 181 High Street,

Willoughby North NSW 2068

Physical Address

Suite 5, 181 High Street,

Willoughby North NSW 2068

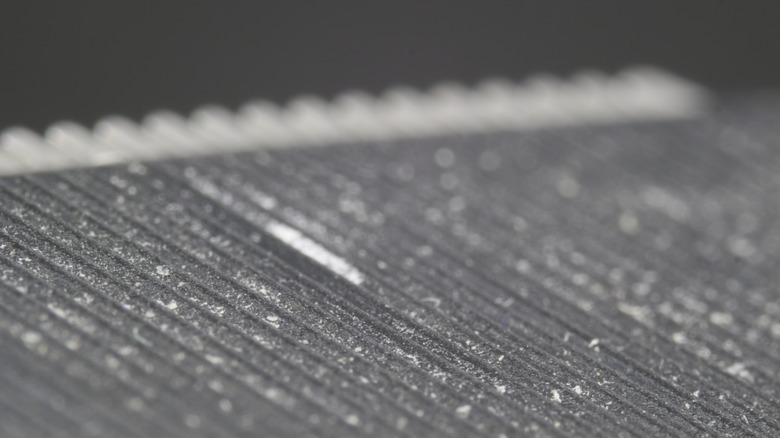

Most objects aren’t really as smooth as you think they are. At the microscopic level, even apparently smooth surfaces are really a landscape of tiny hills and valleys, too small to really see but making a huge difference when it comes to calculating relative motion between two contacting surfaces.

These tiny imperfections in the surfaces interlock, giving rise to the frictional force, which acts in the opposite direction to any movement and must be calculated to determine the net force on the object.

There are a few different types of friction, but kinetic friction is otherwise known as sliding friction, while static friction affects the object before it starts moving and rolling friction specifically relates to rolling objects like wheels.

Learning what kinetic friction means, how to find the appropriate coefficient of friction, and how to calculate it tells you everything you need to know to tackle physics problems involving the force of friction.

The most straightforward kinetic friction definition is: the resistance to motion caused by the contact between a surface and the object moving against it. The force of kinetic friction acts to oppose the motion of the object, so if you push something forward, friction pushes it backwards.

The kinetic fiction force only applies to an object that is moving (hence “kinetic”), and is otherwise known as sliding friction. This is the force that opposes sliding motion (pushing a box across floorboards), and there are specific coefficients of friction for this and other types of friction (such as rolling friction).

The other major type of friction between solids is static friction, and this is the resistance to motion caused by the friction between a still object and a surface. The coefficient of static friction is generally larger than the coefficient of kinetic friction, indicating that the force of friction is weaker for objects that are already in motion.

Working out the kinetic friction force is straightforward on a horizontal surface, but a little more difficult on an inclined surface. For example, take a glass block with a mass of m = 2 kg, being pushed across a horizontal glass surface, 𝜇k = 0.4. You can calculate the kinetic friction force easily using the relation Fn = mg and noting that g = 9.81 m/s2:

(begin{aligned} F_k &= μ_k F_n) (&= μ_k mg) (&= 0.4 × 2 ;text{kg} × 9.81 ;text{m/s}^2) (&= 7.85 ;text{N} end{aligned})

Now imagine the same situation, except the surface is inclined at 20 degrees to the horizontal. The normal force is dependent on the component of the weight of the object directed perpendicular to the surface, which is given by mg cos (θ), where θ is the angle of the incline. Note that mg sin (θ) tells you the force of gravity pulling it down the incline.

With the block in motion, this gives:

(begin{aligned} F_k &= μ_k F_n) (&= μ_k mg ; cos (θ)) (&= 0.4 × 2 ;text{kg} × 9.81 ;text{m/s}^2 × cos (20°)) (&= 7.37 ;text{N} end{aligned})

You can also calculate the coefficient of static friction with a simple experiment. Imagine you’re trying to start pushing or pulling a 5-kg block of wood across concrete. If you record the applied force at the precise moment the box starts moving, you can re-arrange the static friction equation to find the appropriate coefficient of friction for wood and stone. If it takes 30 N of force to move the block, then the maximum for Fs = 30 N, so:

(F_s = μ_s F_n)

Re-arranges to:

(begin{aligned} μ_s &= frac{F_s}{F_n} &= frac{F_s}{mg} &= frac{30 ;text{N}}{5 ;text{kg}×9.81 ;text{m/s}^2} &= frac{30 ;text{N}}{49.05 ;text{N}} &= 0.61 end{aligned})

So the coefficient is around 0.61.